|

Introduction

Having started an interest in

19th century flutes in the mid 1970's, I probably picked up a lot of

flute terms from that period. As a newbie, I hope I can be

forgiven for not being very discerning about all of them. Would it

really matter if these were not the terms they used back in the period

these flutes were made? All things being equal, probably not.

But what if these new terms were misleading, perhaps inviting

us to view and even do things in ways the makers had not intended and would not

approve? Hmmm, not so good. Is it too late to find out?

And if we do find out we've been misled, is it all water under the

bridge, or can we still set the clock back?

The item that prompts this

muse is the humble flute pad - the kind of pad used in the early 19th

century in the keys that we call salt spoons. I learned to call

them purse pads, and to believe that they were made in the manner of a

soft leather purse, filled with wool and the strings tightened.

But over the years, it's increasingly bothered me that the only

references to this seem modern, and the few references I've been able to

find to these pads in the old writings made no mention of this name.

What do we understand by a

purse?

This is my mental image, and

you can immediately see my problem with this mental image. Stuff

that bag firmly with wool, and pull the string tight, and you don't have

a ball - you have a pear. Try to set that into a hemispherical cup

and you'll have a lot of spare material getting in your way.

(Image from http://www.flights-of-fab-fashion-fancy.com/)

So who called them Purse pads

anyway?

Philip Bate, The Flute, 1969,

seems to have set the tone:

They consisted of small

circles of thin kid, drawn up by a running thread round the edge,

like an old-fashioned purse, and stuffed with a ball of fine wool -

indeed they were often called 'purse-pads'. Of course these

could not easily be attached to flat cover-plates, and the natural

corollary to their appearance was the cupped key. At first,

such 'salt-spoon' keys were produced by casting in one piece ...

A slightly earlier book, by

Anthony Baines, Woodwind Instruments, 1957, doesn't seem to use the name

purse pad, but does describe a purse-like construction in a section on

maintaining old flutes.

A quick look at other sources

seems to turn up no other mentions (but if you know of something, make

sure to get in touch!).

And who called them anything

else?

The earliest reference (not

surprisingly) seems to be the inventor of the devices, and I'm much

obliged to MarkP from the Chiff & Fipple forum for this information.

Mark quotes Kroll (The Clarinet, 1965). Kroll is talking about

Ivan Muller (more accurately

Iwan Müller),

who, around 1810, invented this style of pad in order to make the

clarinet fully chromatic:

His pads were made of gut

or leather stuffed with wool, as generally used today. Earlier pads

consisted of slices of soft leather or felt, stuck with glue or

sealing wax to the underside of the flap. Muller wrote in this

connection: 'In regard to the keys, I have invented a kind of

elastic "ball" and, having used it for several years, I am

convinced of its efficacy. There ¡s no risk with these pads that

either a moist or a dry atmosphere will make the keys unworkable;

they close the holes effectively under all conditions and make no

noise'

Aha! Elastic "ball",

eh? But no mention of purses!

An advertisement by Clementi & Co in the Fourteenth Edition

of Wragg's Improved Flute Preceptor, Op. 6, 1818 for Nicholson's Improved Flutes

mentions Elastic Plugs.

Thomas Lindsay,

1828, uses the expression "Elastic Ball" in the article twice,

and also makes two references to "Elastic Plug Keys". The

only references to "purse" in that article are mine, in side comments.

Hmmm.

Nicholson, the great flute

player and teacher, writing in 1836,

mentions:

The elastic plugs

to all (except the lower C keys), and double springs, are great

improvements;

As late as 1851, the

Exhibition Catalog mentions flutes

by Kohler with 8 Elastic Plug keys

Rockstro, much later, in The

Flute, 1889, describes them as "pads, or cushions, of spherical form".

"Of spherical form?!". After reading all the other accounts, one

is inclined to respond: "Balls, Rockstro, balls!"

So it seems "elastic balls"

or "elastic plug keys" were the common expressions of the time, and so

far we've found absolutely no reference to "purse pads" or a description

of construction that would prompt the use of such a name. Curiouser and curiouser.

Now why "elastic"?

"Balls" we can understand -

it describes the shape. But what's the obsession with "elastic"

all about? To find that out, we have to consider what the

alternatives were at the time. Coming out of the previous baroque

era, we had the leather flap key - just some thin leather stuck to a

flat flap, sealing over a flattened section of wood with the hole in it.

Fine for a 1-key flute, but increasingly unreliable as you added more

and more keys. You can see why Muller was in trouble with his

chromatic clarinet.

But in 1785, Richard Potter

patented his "Potter's German Flute" with a new system of metal

"valves", which today we call Pewter Plugs. (Hmmm, I wonder when

that name got going?) So there were two unique features of

Muller's invention - they were balls and they were soft. Indeed,

can we hear him making reference to Potter's pewter plugs in that quote

above?

There ¡s no risk with

these pads that either a moist or a dry atmosphere will make the

keys unworkable; they close the holes effectively under all

conditions and make no noise'

Pewter plugs, being

non-elastic, can give trouble when the weather is very dry or moist, and

the metal-lined hole is made oval by wood movement. And of course,

being metal closing on metal, they were noisy.

Thomas Lindsay,

1828, agrees with Muller:

OF THE VARIOUS

DESCRIPTIONS OF KEYS, used by different makers, he [the writer -

Lindsay] gives a very decided preference to those with the

Elastic Plugs or padded Keys, not only because he considers them

best adapted for stopping, but also for the powerful recommendation

which they carry with them, - that of being used without noise from

the reaction of the key, and the additional fact that they are less

liable to get out of order than either the flat-leathered keys, or

those with Metal Plugs, so truly disagreeable for their noise and

clatter.

These days of course we are

used to pads being soft, stuffed and therefore elastic. So the

unique feature for us comes down to their shape.

Rubbing salt into the

spoons?

Notice that expression

"Elastic Plug Key" - which we now understand was their name for the kind

of key that uses "Elastic Balls". But, hang on, we call those

salt-spoon keys! A search shows that they didn't - "salt spoons"

is probably another 20th centuryism! We might leave that one to

deal with later, other than to note the quote from Bate (above) where he

called them salt spoons. Hmmm, was Philip a serial misleader?

(Aside. Philip was

actually a broadcaster, a field I shared with him. One of the

challenges a broadcaster faces daily is finding ways to get an image

over to the listener without benefit of video. Perhaps we're

seeing the broadcasters' mind at work?)

What's so special about

these pads?

Are we really worried about

what these pads were called and how they were made? Surely if we

wanted to pad one of these flutes these days, we'd just use a regular

flute pad?

Unfortunately, it's not quite

that simple. Sometimes you can get away with a regular flute pad

with these old flutes, but not always. These pads were unique.

The cup was a hemisphere, as was the depression in the wood into which

the pad had to close. Put two hemispheres together, and you've got

a sphere, as Rockstro told us. And nobody makes spherical pads

these days. Modern pads are fat discs, with flat tops and bottoms.

Apart from shape, what is

critical about these pads is the size. Too big and it won't go in

the cup or the hole. Too small and it will compress, allowing the

rim of the keycup to clack against the wood on closing. Perhaps

not on the day you install them, but a few months later! Grrrr!

But it does have to be said

that, when they were good, they were very, very good. Silent,

airtight, and more gentle on the air-flow than our modern pads.

Nice!

How long were these pads in

vogue for?

As we've seen, essentially

the same period as we find saltspoon (um, sorry, elastic plug) keys.

And that is a surprisingly long period. Since Müller invented them

around 1810, we can safely take that as the start of the period.

The end is harder to pick.

We know Boehm introduced card-backed pads for his conical open-keyed

flute in 1832. (Elastic balls could only work on flutes with

normally closed holes, as they soon lose their shape if the key was left

open. That's why the low C and C# keys on 8-key flutes continued

to use pewter plugs.) After a while, card-backed pads started to

make inroads into the 8-key style flute too, and you could tell those

flutes that were designed to use them. Typically, their cups are

lower and flatter, typically with the end of the shaft pointed and extending to the

centre of the cup, rather than terminating on the side of the cup.

Further, the seats (the hole in the wood into which the pad closed)

changed. Instead of the hemispherical hole, it became typically

volcano shaped, providing a clear sharp edge for a flat pad to close

against.

Not everyone went over to the

pointed cups with the card-backed pads and the volcano seats. We

find flutes that have saltspoon-style keys at least as late as this

Rudall Carte in 1898:

Rudall Carte 7120, Cocus and nickel

silver, McGee Research Collection

But I'm not so sure this flute did use "elastic balls".

The keys are broadly salt-spoon-shaped, but the cups, while still rounded, are

rather flatter than the hemisphere on the earlier ones. And the

holes are more flat bottomed than hemispherical or volcanic.

Further, the holes through to the bore from the base of the seat are

much bigger than could have supported an elastic ball. It would

have flowed right in. I think this flute was made to use modern

card-backed pads (which had been around for well over 50 years by then),

but designed to resemble a flute with the elastic plug keys.

Tricky!

So I guess the hunt is on for the end of the elastic

ball period. Such a flute will have these characteristics:

-

a truly hemispherical cup (not a flattened

hemisphere or a pointed cup)

-

a truly hemispherical seat in the wood (not a

flat-bottom ledge or a volcano)

-

a relatively small hole through to the bore (smaller

than the nearby finger holes).

What's interesting here is that we have to look at cup,

seat and hole to make the judgement. In the past, I think

people have made assumptions without consideration of all three.

So how were these elastic balls made?

Unfortunately, the only

references to making these pads I've been able to find so far are the

20th century ones, from

Bate and Baines.

(These gentlemen knew each other, incidentally, and I was fortunate to

meet them both. Anthony Baines was the curator of the Bate

collection at Oxford when I went there in 1974, having met Philip Bate

while hanging out with flute dealer Paul Davis.)

So, in the absence of any

contemporary report, we're going to have to rely on forensic evidence -

dissecting some pads in the hope of finding clues to their construction.

Fortunately, I have a few such pads taken from original flutes.

Hopefully I have enough! Just in case, I've put out the word -

don't chuck out those old pads just yet!

Of course we have to guard

against the possibility that the methods of construction changed over

the 40 or more years that these pads were in use. So there might

be more than one form of construction. We may have to consider

this investigation as ongoing, until we are satisfied that we have the

full story. I'd want to apply McGee's Razor:

Let me apologise in advance

if I've inadvertently snitched someone else's razor. I'll happily

put it back if you can find me a name!

It does remind me of the old

saying:

-

one log can't burn

-

two logs won't burn

-

three logs might burn

-

four logs will burn, but

-

five logs a fire makes.

The investigation

I took an Eb pad from a flute

by Weekes of Plymouth, circa 1844, and submersed it in alcohol.

The hope was that it would dissolve the shellac on the back of the pad,

enabling me to see how it has been made. There was some risk that it

would completely disassociate the pad, but maybe that wouldn't be a bad thing.

I chose the Eb key, as it is big, and should be easier to dissect and

observe. If alcohol proved too mild, I was going to move on to acetone.

Next day and immediate success! But

immediate confusion too. What I had assumed was a red shellac used

to set the key in the cup now appears to be something separate under

the shellac layer. (And I don't remember the shellac in the key

being bright red when I replaced the pads). The alcohol dissolved the

shellac overnight, as I had hoped, but it didn't dissolve the red goup,

just dissociated it somewhat. Perhaps one of the red goup's constituents

was alcohol soluble or alcohol affected. Looking at the other pads

in the set, all have the red goup, covered to varying degrees by the

dark but relatively colourless shellac.

The other interesting thing

about the red goup is that it appears to be concentrated on a section

in the middle of the back of the pad where there is no leather.

Aha! Could it be a sealer perhaps to keep the finished pad safe

until it gets installed in a key? (Safe from what? Coming

apart, or insect attack perhaps - one of the pads did have signs of

insect infestation.) Or moisture? Or is it intended to prevent the hot

melted shellac from soaking into the wool inside the pad, perhaps

rendering the pad hard, or perhaps robbing adhesion to the inside of the

cup? More and more interesting!

Now, what's red and was used

in the 19th century to seal things. Um, how about "sealing wax"?

Wax probably wouldn't dissolve in alcohol, so that works.

Now, wait a minute! Did

I just say "a section in the middle of the back of the pad where there

is no leather"? I sure did, and sure enough there is such a

section. But aren't these pads supposed to be drawn tight?

Indeed, tight, but that doesn't necessarily mean closed. Aha, so

there's a possible solution to the bunching up problem I outlined above

- cut the disc of leather too small to meet around the back, and then

fill the remaining hole with something that won't soak into the wool,

but that will prevent shellac from doing so. So what is bunching

up the leather?

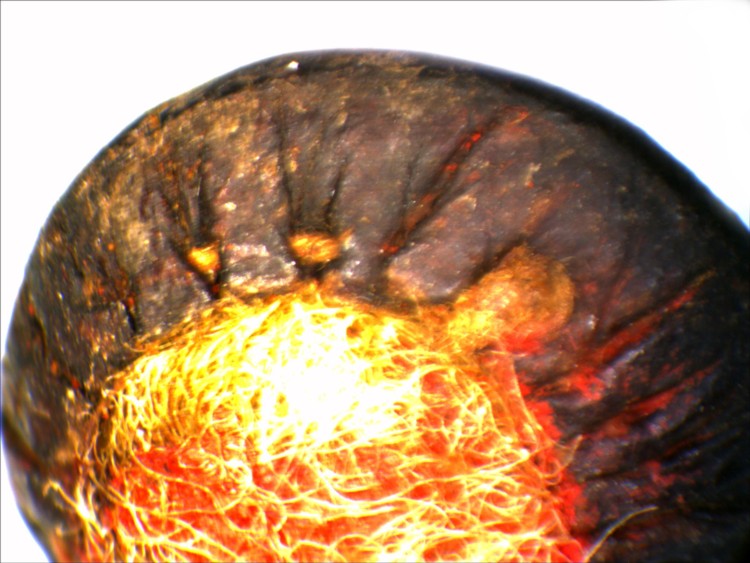

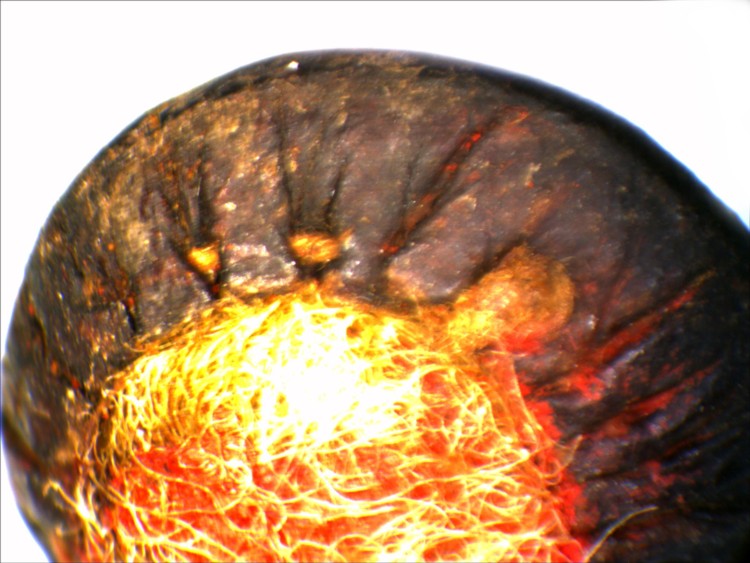

The microscope image reveals

all. We can make out all

those details:

-

the leather increasingly

bunched up as it comes around to the back of the pad.

-

a much larger "hole" at

the back of the pad than the descriptor "purse" might suggest

-

a running stitch around

the edge of the leather, pulled tight and knotted, just like Philip

Bate said (that lump on the

right is the knot)

-

the red goup at the

bottom, and remnants of the red goup in the valleys between the

ridges of leather (particularly noticeable at the right)

-

strands of wool (yellow)

sticking out through the red goup.

Ah, so it's official.

They were sewn, broadly like purses, but with some important differences:

-

the big hole at the back,

to avoid the bunch-up of leather that would make it impossible to

fit nicely in a hemispherical cup. A partially closed

purse with no neck.

-

the mystery red goup,

presumably used to seal the back of the pad.

So how far in does this red

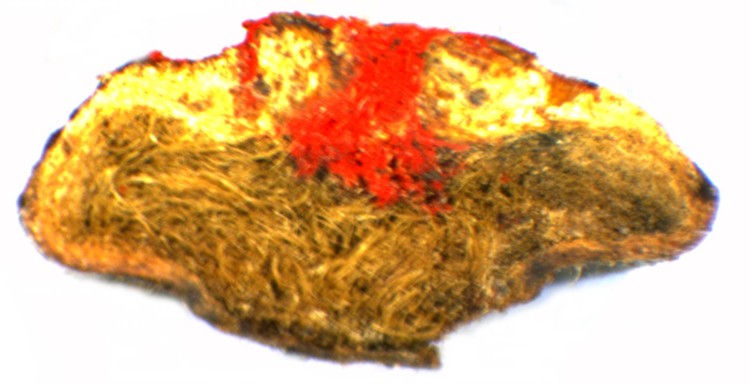

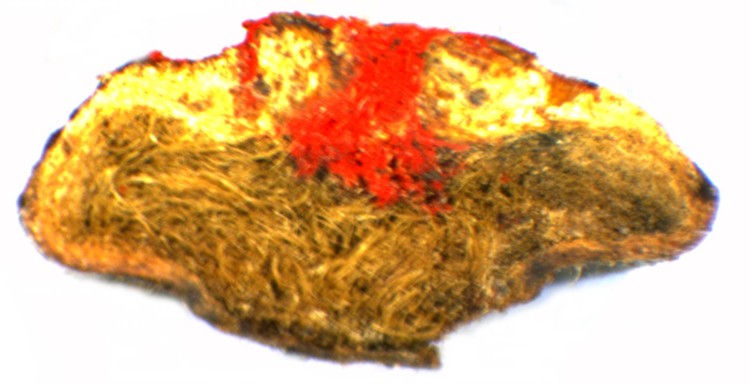

goup go? I cut through the middle of another of the pads with a scalpel:

The back of the pad, the part that

fits in the key cup, is at the top. We can see:

-

at the top, in lemon

yellow, the leather bunched up on both sides

-

the leather continuing around

the rest of the pad, in orange, with dark outlining.

-

the compressed wool in the

centre.

-

the thread, seen here in circular

cross section, resembling two eyes, in the middle of the two lumps of

bunched up leather at right and left top

-

The hole in the middle of the

back of the pad, filled

with red goup

-

Red goup spilling over the top, and

soaking into gaps between the wool in the centre.

The importance of the point about

leather bunching up is made clear in this image. See how the relatively

thin leather (the orange layer around the sides and bottom) becomes about three

times thicker in the areas at the top around the thread. You just couldn't

allow that purse to close fully. Indeed, interesting to see that this

smaller Bb ball is more closed than the larger Eb pad we see further up.

Could be variability in manufacture, or maybe the bigger the pad, the less you

can afford to close the gap.

Now, pinch yourself and remind

yourself you are looking at a ball! Um, not very round, is it? You

can see that it would have been much bigger when new - follow the curve at the top to get

some impression. Assuming the circa 1844 date for Weekes, this pad has

been in that flute under spring pressure for 163 years. Some of the pads

leaked, but a few of them were still airtight, even in the view of the

Magnahelic Flute Leakage Detector, which can measure the airflow through

the sworls of my fingerprints. Not bad, eh?

You can see a broad nipple at

the bottom where the ball has also pressed into the hole at the bottom

of the keyhole. You can also see here that Weekes was moving

towards flat-bottomed holes which seems to have preceded volcano seats.

The area surrounding the nipple is closer to flat than hemispherical.

That shape still works fine with "elastic balls", but this flute was one

I was able to use standard modern pads for without difficulty and to the

entire satisfaction of the fussy Magnahelic.

The stuffing, incidentally,

is probably wool, but about 150% coarser than the only raw wool I had to

compare it with. But we grow fine wools in Australia, more suited

to soft jumpers than hard-wearing carpets, so that probably accounts for

the difference I'm seeing.

A better metaphor?

If we're looking for a better

metaphor in the fabric arts for how these pads are made, perhaps it

would be the Suffolk Puff, called the Yo-Yo in US quilting circles.

As you can see, the method is the same, but the fabric doesn't continue

beyond the stitching any further than needed to prevent the stitching

tearing out.

| A

Suffolk Puff under construction. Fill that with wool

and it will become a ball, not a pear! Click on the link

above to see how it's made. |

|

So what should we call them

in future?

-

Well, as you can probably

gather, I'm not completely

happy with "purse pads". That for me conjures up

quite the wrong

mental image, and invites us therefore to go quite down the wrong path, with

the result that it all ends up going pear-shaped, as they say in the

classics. You don't "purse" your lips with your mouth open!

And the important thing isn't how the pad is made, but that it's

spherical. It's one thing to have a name that isn't original,

but quite another to have one that is both unoriginal and misleading.

-

Elastic ball? Hmmm,

accurate certainly, but not that attractive, is it? I'm inclined to leave the subject

of balls to

Amnesty International, where it's done so much good around the

world.

-

Elastic plug? Not

inspiring either. It does make the distinction between plugs

and pads - plugs fill a hole, while pads cover holes over. But

the word plug is not familiar to us in this context, and might prove

a barrier to acceptance.

-

Pads? Naah, all

pads are pads, and these are special pads.

-

Stuffed pads?

Again, all pads are stuffed, so it doesn't help.

-

Spherical pads?

That's possible, even if I made fun of Rockstro above. (Hey,

he deserves it!) They are spherical, and they do look like pads

(even if they allegedly act like plugs). Nothing misleading. The

name differentiates them clearly from the later card-backed pads

which is the distinction that needs to be made.

Could we learn to live with "Spherical Pads"?

-

Or "ball pads"?

-

Sewn pads, perhaps,

illustrating the method of manufacture, but not bringing in a

confusion about bunched-up leather.

-

Or "Puff pads", drawing

on the Suffolk Puff metaphor we discussed above? Probably too

specialised a term to make a broadly useful metaphor?

-

Other, please specify.

If you have suggestions, claim your place in history!

I'm attracted to spherical,

because that is the important thing about these pads. But I don't know whether we can

learn to live with that name. We'd have a lot of unlearning to do -

at the time of writing I've lived with "purse pads" for over 35 years.

But on the face of the evidence before us, it's only part of the story

and rather misleading. We could do better, and I'm plumbing for

"spherical pads" until someone comes up with something equally

meaningful but maybe more euphonious!

And the keys?

I'm not so offended by the

name salt-spoon key, even if it was not what they called it at the time.

It's descriptive (at least for those who have actually seen a saltspoon,

and that might be a decreasing number in these days of sea-salt grinders

and plastic iodised salt dispensers!). That lack of familiarity might

prove to be the problem for

continuing meaningful use of the term! How many of us have a

salt-spoon in the cruet set on our dining table today? (I would be

confident, having sat at Philip Bate's kitchen table, that, had I

thought to look, Mrs Bate would have had!)

The period term "elastic plug

keys" would only make sense if we used the term "elastic plugs" for the

pads. There could be an argument for calling them "spherical pad

keys", or "hemisphere keys", to fit in with spherical pads?

I'd be happy with "hemisphere

keys" and "spherical pads". But, more importantly, would you?

It's not over yet, folks!

Did I mention above that this

might have to be an ongoing investigation, because these pads were

probably made by a lot of people over a few decades? Even as I

write these terminal words, the prophecy seems to have come true.

Californian repairer Jon Cornia sliced up some pads from a newly arrived

Nicholson's Improved and reports that, similar to our findings, the pads

are sewn, with a running stitch around the edge of the leather, and

pulled tight, but with a gap remaining, as we have found. His pads do not seem to

have had the sealing wax treatment however. Perhaps that was a

regional specialty, or perhaps mine were replacement pads, that could

expect many years rolling around free before being secured in a key.

And Weekes being in Plymouth, those years might even have involved a

life on the rolling wave!

What remains to be done?

It would be good if we could

recover (or if necessary, reinvent) the formula for sizing these balls,

to make making replacement ones a bit easier. I imagine that we

should be able to relate cup diameter with the size of the disc of

leather needed, plus establish how far in from the edge the stitches

run, and the distance between stitches. We'll probably need to

take measurements from a wide range of cup sizes to establish the system

Hopefully others will now

carefully dissect their old pads, and advise us what they find. It

would be good to know:

-

the maker of the

flute,

-

the flute's age or

age range (if known)

-

sewn in the same

manner as above?

-

the shape of the

cup (if not hemispherical)

-

the shape of the

seat (hemisphere, flat-bottomed, volcano, other?)

-

the size of the cup

-

the size of the

hole at the bottom of the seat

-

any sign of goup

filling the hole at the back of the pad?

-

how big a hole is

left at the back of the pad?

-

the diameter of the

disc of leather used to make it

-

how far in from the

edge the running stitch runs

-

how long are the

stitches (and are they the same inside and out?)

We may strike a shrinkage or

compression issue in regard to the size of the leather disc, and may

need to carry out some experiments to confirm how much leather is needed

for a certain sized cup. But let's exhaust the forensic

possibilities first!

Conclusion

Well, that turned out to have

a few surprises, didn't it. They were clearly called elastic balls

or plugs, not purse pads as we have confidently called them since the

1960's. And the keys were called elastic plug keys, not saltspoons.

The pads were constructed more like Suffolk Puffs than purses, and some

(at least) incorporated sealing wax as part of the process.

And we saw that not all "saltspoon"

key flutes actually were intended to use elastic ball pads - you have to

take into account the cup, the seat and the hole to make a formal

diagnosis.

And we now have the right and

responsibility to decide what to call them in future. I look

forward to some spirited discussions!

|