|

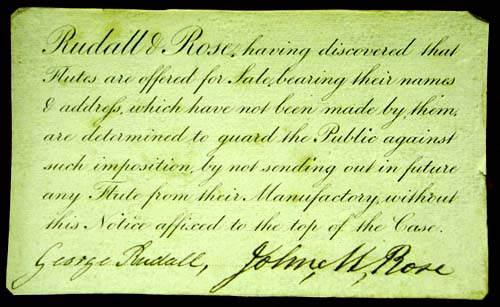

Look inside the lid of the stylish vaulted cases provided with their

flutes by Rudall & Rose and you'll find an interesting

certificate. It reads:

"Rudall & Rose, having discovered that Flutes are

offered for Sale bearing their names & addrefs, which have not

been made by them, are determined to guard the Public against such

imposition, by not sending out in future any Flute from their

Manufactory without this Notice affixed to the top of the Case."

The certificate is signed:

George Rudall, John, M, Rose

and, in later days, carries the date. Here's an

example of such a certificate, from a Bb flute in the Royal Northern

College of Music in Manchester.

Well, is it for real? Were there really other makers

passing off their flutes as having been made by the illustrious firm of

Rudall and Rose? Or was it just clever merchandising - pretend your

product is so good that others are imitating it? We think we now

have some real live evidence to put before you ....

Contemporary evidence

But before we look at our smoking gun, let's look for

corroborating evidence from writers of around that time. From

Lindsay's "A Few Practical Hints"

(London, 1829), we find that the practice of faking flutes by well-known

makers was well documented:

"But incapacity is not the whole "head and front of their offending," for these sort of gentry often go a step

further, and having no reputation of their own, they make free to borrow

that of various respectable and established maker's, by stamping their names upon

the trash vamped up in the manner we have described, and so doubly impose upon the

unwary.

In this way, the names of Messrs. CLEMENTI

and Co., Messrs. MONZANI

and Co., Mr. NICHOLSON, and Mr.

POTTER have been successively used by the unprincipled and designing, sometimes either omitting, adding, or altering a single letter in the

orthography of the name, so as to evade the operation of the Law, in the event of

the fraud being detected. Indeed to such an extent have these nefarious practices been carried on, with reference to the last mentioned individual, in particular, that they must of necessity have subjected him to much mortification and loss: there is scarcely

in town a shop window of the description alluded to, which has not an abundance

of " Potter's Flutes" exposed for sale, not one in six of which are legitimate, but known amongst the

flute-making trade by the unequivocal denomination of "bastard Potters."

The same system has been followed in regard to Mr.

DROUET'S manufacture, and the comparatively inconsiderable number of Flutes, which his short sojourn in this country enabled him to finish, has, even on a moderate computation, been thus surreptitiously increased five-fold, for notwithstanding all

the "fine toned Flutes by Drouet," which are ticketed up in every street, scarcely a

genuine DROUET Flute is now to be met with."

But more than that, Lindsay reveals the practice of foisting badly-made

flutes off as the work of others. He precedes the above with:

"It is a fact that no

wooden, musical instrument can be expected to prove perfect, unless

manufactured from well-seasoned materials; but, in despite of this

truth, it is notorious that nine-tenths of those instruments which are

daily exhibited in the Sale-shop window are made by needy workmen,

without credit, who have neither capital to carry into the market to

purchase a stock of material, a good model to work from, nor yet

character as tradesmen at stake. The consequence is that a single

log of wood is often purchased on one day, is sawn into lengths the

next, and subsequently turned, bored, mounted with what is called

silver, and otherwise metamorphosed, in the course of the same week,

into an apparently elegant Flute, - but without tone, without

intonation, "sans everything," in short, but external

appearance to recommend it. This Flute, with all its faults and

imperfections on its head is then sold to the Pawnbroker, or Salesman,

for whatever price it will fetch, and immediately offered to the public

as an instrument of the very first order, an article of undoubted vertú!"

Other writers around that time have made the same and similar

claims But claims are one thing - it would be nice to see a real

live example (pauses for drum roll) ....

The Peoples Exhibit No 1

The flute below was turned up in late 2002 in a second-hand store in

Vancouver, Canada, by my good friend and research colleague Adrian

Duncan. Several weeks later it landed on my doorstep. It's

currently "assisting authorities with their

enquiries".

Compared to what, m'Lord?

It has to be said that Rudall & Rose have not made it easy for us

to spot a fraud. Their output, some 5800 flutes before they became

Rudall Rose & Co, is enormously varied in every conceivable

feature. We'll be relying on evidence thrown up in our Rudall, Rose

or Carte Models Study, but we have to concede that virtually every flute

so far investigated is different in at least some way from every other.

Old Fake or Crummy Repair?

The flute in question is in bad shape. Only one key remains on

the body section and most blocks are not integral with the body.

What is original work and what is more recent? We need to tread

cautiously...

How to proceed?

Our approach will be to look at every detail of the flute, comparing it

to what we might expect of an authentic Rudall. We'll certainly

point to the things that we find anomalous, before trying to

determine if the flute is authentic. If you know better about a

point we raise, we want to hear from you. We'll work our way down

the flute, bringing every matter of interest to your attention.

THE HEAD

The cap

Starting at the top we meet the cap. Now the cap plays no part in

the acoustics of the instrument (apart from being our way to move the

stopper). It's essentially a functional item with some decorative

properties. It seems to me that, at 11.2mm, this cap is thicker than the

usual Rudall cap and employs different decoration (see below).

|

The Indicator

The stopper shaft protrudes through the cap and acts as an indicator

of stopper position. The classic Rudall indicator is a ball,

sitting astride a sloping podium. The ball on this indicator is

not round, nor is the podium sloping.

|

|

The Stopper

Further, the shaft would normally have a flange at the back of the

cork, and the threaded section that screws into the cork would be

tapered. The cork would normally be about twice this length.

The shaft varies between 12.3 and 11.7mm (suggesting it is

hand-chased and so probably from the period), with the section

entering the cork about 8.3mm. Rudall's seemed to go more often

for a shaft about 11mm.

The thread pitch though is interesting - it appears to be 17 TPI.

Not a common pitch.

The top ring

This is probably a poor repair. It is porous on the outside and perforated on the

inside. There are none of the common Rudall thread

grooves on the wood beneath.

The head

The head, at 133mm, is very short, compared to the average 160mm,

and minimum 147mm thrown up in the RRC study. Why waste wood if

you're doing a fake? Most of the "missing" wood is

from above the embouchure.

Embouchure

The embouchure hole is crudely cut. The hole in the metal liner

is substantially bigger than the hole in the wood, and not set well with

it.

Lower Ring

Normally, on a Rudall, the two rings between head and barrel take the

form of rings with a flange on the visible side. This is just a plain ring.

Male slide gap

The gap in the end of the head which accepts the protruding barrel slide is

not concentric with either the ring or liner. Uncharacteristically

shoddy work.

Liner

The head liner is of yellow brass, apparently soft soldered, with the

thin plating completely worn away.

THE BARREL

|

Barrel slide

It's thin yellow brass, with no sign of the usual decorative

sleeve. The leading edge has been compressed to procure

air-tightness. The lower end protrudes well into socket, rather

than being rolled to prevent withdrawal, to the extent that a 1mm gap

remains when the body tenon is pushed home. |

|

Top ring

This ring is more narrow than the matching adjacent ring on the head, protrudes more

and again has no flange.

No Name

The barrel on a Rudall flute normally carries the maker's name.

Bottom ring

Normally the widest ring; on this flute is of intermediate size.

Again, there are no grooves in the underlying wood.

THE Left Hand Section

The Maker's Mark

Very interesting. RUDAI L & ROSE, with the final L in RUDAI L excessively spaced,

as if the penultimate letter was also L. The final L also a little

twisted.

|

| ROSE is drooping; LONDON rising.

No Address. No Serial

Number.

|

|

Top block

Normally one rounded bead serves as both hinge block for Bb and guide

block for upper c; only the upper half of the c guide block remains.

It appears crudely formed.

|

|

A massive rectilinear hinge block has been grafted on for Bb. It

is crude and misshapen in every dimension, surface and edge. Its

slot is wide, wedge-shaped and rough, and extends well below the

surface. It is probably a very bad repair. C Hinge Block

The C Hinge block is integral with the body, but again poorly

formed. No striker plate for the spring.

The C Cork Dot

While cork dot silencers are common on Rudalls, the Long C doesn't

normally have one. The cork dot on this flute (visible at the right

of the image above) is very badly formed.

G# Block and Key

|

|

The G# block is also integral with the body, but unusual in that both

of its ends are curved, whereas on most flutes of the period the lower end

cuts tangentially back to the side of the body. The key (the only

body key left) is unusual too in that it is slightly asymmetric, with a

cutaway to reduce interference with the third finger. It looks a little

apologetic though! |

|

A small chip from the inner edge of the G# seat probably occurred at the time

of making. The hinge pin shows drawplate marks and has been cut off

quite crudely. The key is cast adequately but the business end of

the spring is poorly finished. Again no striker plate.

THE RIGHT HAND SECTION

The ring

Of more normal dimensions, but again no grooves in the underlying wood.

The Split

A wide split has occurred, extending 50mm or more down the

section. This suggests substantial shrinkage of the wood, with the

ring left providing no support. There appear to be two other lesser

splits to the socket area. Such splitting in unlined sections is

rare in flutes made from adequately seasoned timbers.

The socket

Something funny about this socket - it's 4mm deeper than the tenon is

long. Very sloppy, very uncharacteristic.

The Maker's Mark

A bit obscured by the rough work of the subsequent repairer, but

essentially the same as the marks on the upper body and foot. Again

definitely "RUDAI L".

|

Blocks

The blocks for both Short and Long F have been added to the flute, but when

is impossible to establish. Both jobs display the worst possible

workmanship. There are traces of a former guide block for Long

F.

And signs of a careless cut with a dovetail saw on the Short F...

|

|

THE FOOT

The Foot, perhaps the hardest part of a flute to do well, is actually

in better shape and is more well made than the rest of the

instrument. None-the-less, there are still issues to consider:

The Socket

|

|

As above, the socket has a wide split, suggesting shrinking wood, and

the socket is a little deeper than the tenon is long. The ring is

better fitted however, and there is a thread groove in the wood under

it. |

|

Eb Key

The Eb key conforms to the normal Rudall outline, but is mounted

without a striker plate for the spring. The slot is reasonably well

cut and pin installed well. The key seat is countersunk and cut

better than the remaining seats.

The C & C# touch shafts

These are well enough made, but seem a little wide in the touch area

for Rudall's. Because the C and C# holes were not set in line, the

two shafts do not run quite parallel. Again there are no striker

plates for the springs to bear upon.

The Pewter Plugs

|

|

These close onto round horizontally- mounted plates, apparently held

in place by adhesive. Rudall plates are usually square, mounted at

an angle and secured with tiny screws. Closing is not great.

Neither is opening. The lower plug does not open far enough. |

|

Maker's Mark

The final L in RUDAI L excessively spaced and twisted, ROSE

drooping. LONDON horizontal.

General Matters

In addition to the specific matters above, these general matters need

explanation:

Timber

The timber could be cocus. It appears to have been stained

darker, but most of the staining has been removed during later work.

The finish is poor with many visible file, chisel and sanding marks, but

it is impossible to determine which are original and which are subsequent

abuse.

Nickel Silver

Nickel silver was not so common in the Rudall & Rose period.

It probably is explained by Lindsay's comment "mounted with what is called

silver". It would seem consistent with a fake.

Hole Liners

The liners on the six finger holes are not rings set in as usual but tubes within the holes.

The tubes

appear to be pewter - the material is certainly softer than silver and

more grey. The tubes on holes 1 & 2 are not flush with the

surface of the wood. The tube on hole 2 projects into bore, while

the tubes on the other holes do not make

it to the bore, leaving a rather nasty surprise for air molecules that

might have wanted to exit there.

Key seats

The key seats are domed, rather than funnel-shaped (for purse-pads) or conical (for

card-backed pads). The holes not always concentric with seats.

It's rough work.

Striker plates

None of the keys have striker plates to take the spring load.

This is unusual; indeed flutes in the Rudall & Rose period were

commonly fitted with double springs (see Rudall & Rose No 519).

Cork Dots

On a regular Rudall, you might expect to find cork dot silencers under

the Bb, G# and Short F keys, but certainly not under the upper C, long F

or foot keys. On this flute only upper C has a dot, and it very

badly formed.

The Name Stamps

Perhaps the most damning evidence. "RUDALL" spelt

"RUDAI L". Recall Lindsay's comment: "sometimes either omitting, adding, or altering a single letter in the

orthography of the name, so as to evade the operation of the Law, in the event of

the fraud being detected".

The same stamp appearing in three places (normally Rudalls have a different

stamp on the upper body). No address (why tempt fate by telling

the owner where to bring the flute for service!). No serial number

(again to avoid embarrassment when Mr. Rudall appears in court with the

factory records).

Best Match with a Known Rudall

So is it like any Rudall we've ever seen? With some

reservations (particularly in terms of quality), yes. The best

match so far is R&R No 5047, No 592 in the Edinburgh

University Collection of Musical Instruments. Firstly, an exaggerated

image of the bore:

And the size and position of holes:

There are clear differences certainly, but probably relatively

insignificant in performance terms. We haven't got as far as

testing this flute yet (you've seen the condition it's in!) but I would

expect it to perform well if tidied up.

The apprentice theory

So how did this flute come about? One possibility to be

considered is that it actually came from the Rudall works - either as a

training exercise for an apprentice or from an enterprising workman

working through his lunch hour. But the blatantly fraudulent

maker's mark blows that theory out of the water.

The conclusion

I think the evidence is overwhelming - this is a fake! What a

wonderful thing to find - clear evidence that Rudalls (and presumably

other flutes) were being faked and that Lindsay wasn't just making this

stuff up.

Despite my confidence, don't be bullied. If you feel you can

poke holes in the evidence, or conversely if you can spot stuff I've

missed, get in contact.

Acknowledgement

Thanks to my good friend and colleague, Adrian Duncan, in Vancouver

Canada for finding this little number, entrusting it to our deliberations

and permitting this publication.

|

|

Return to McGee Flutes

Contents Page Created:1 February

2003 |

|