Introduction

Siccama's 1845 Patent application has been criticised harshly by

Rockstro and more recent writers on the grounds that it was for four

instruments, only one of which ever came to anything. As I

think

you'll see, this was mischievously disingenuous of Rockstro, and going

along with it less than rigorous on behalf of his

repetiteurs.

I think we'll find that Siccama's patent was more in the way of an

"omnibus" protection document - Siccama had a range of ideas he thought

had merit and cobbled them all into this application. Is that

evidence that all of the described instruments were ever intended

for manufacture? I think not. So what unites this

omnibus

full of notions? Unfortunately Siccama does not make that

clear,

and perhaps nobody has thought to look. So, I'll hazard my

guess

and you can see if it holds water.

The unifying theme

I'd say the unifying theme is "Big holes, well placed, and how to cover

them". Up to then the English had been playing medium to

large

hole 8-key flutes derived from Nicholson's Improved flute.

Boehm

had come up with his conical ring-key concept in London in 1831 and

improved it in 1832, but it hadn't caught on. There was

renewed

interest in it in 1843 when Rudall & Rose started manufacturing

it. But with the narrow bore and medium sized holes it still

couldn't compete with a typical English 8-key in power, even though it

ran rings around them in tuning, tone and uniformity. The

complexity of

the instrument and its change to fingering were also roundly criticised

at the

time. So it must have been on many minds that the way forward

was

to combine the best features and reject the worst features of

both. It shouldn't take long to come up with a list of

features,

e.g.:

From

the 8-key:

and

from the conical Boehm:

- uniform size of holes

- for uniformity of response and tone

- proper location of

holes, for good tuning

- comfortable reach, for

ease of playing

We can visualise Siccama as one of many contemplating the issues,

scribbling ideas in the margins of the Musical Times. Ideas

would

be conceived, developed, rejected, modified, culled, and finally a

short list would emerge. If any of the ideas looked really

promising, a wise man

would seek to patent them to prevent others profiting from his

work. If you're going to patent the best of your ideas, you

might

as well throw the second-best in too.

So, I'd say we're looking at the culmination of Siccama's feasibility

investigation - a number of ways that a common set of holes could be

controlled to achieve as many of the goals listed above as

possible. So in examining his patent we can glimpse more than

four flutes and more than a bunch of ideas. We're seeing what

had

been going through Siccama's mind in the year or so leading up to the

patent application: how can 8 fingers and 2 thumbs control 11

holes?

Housekeeping

In looking at the patent, we'll leave out a lot of the traditional

patent formalities ("To all

to whom these presents shall come ...." etc.) and get

straight

down to the business bit.

The drawings appended to the patent document are absolutely huge - like

road maps

- and will not reproduce adequately on screen. Consequently,

I've

chosen to

represent them as schematic drawings similar to those seen elsewhere on

this web page. Wherever Siccama refers to a point in the

drawing

with

a reference number, the new drawings include that point.

You'll probably find the original text a bit less than riveting -- you

have to remember that a patent document is not promotional flummery but

more of a legal document guarding against the possibility of someone

snitching his intellectual property before he has a chance to take the

benefit of it. And Siccama was a professor of languages, so

we

can expect that to supervene a stratum of formality, to which they are

no-doubt predisposed in Oxford. So I'll interpose comments as

I

see fit to try to make the document more comprehensible - anything from

me will be [in square brackets] or otherwise marked.

SICCAMA'S

SPECIFICATION.

[This

is the part of a patent

application in which the matters to be protected are to be set

out. We note that it is an omnibus-full of matters, rather

than

"4 flutes".]

My Invention relates, first, to closing the A natural and the lower E

note each with a key, for the purpose of enabling me to enlarge those

holes to correspond with the other holes, the fingering for those notes

remaining the same, or nearly so, as in the ordinary flute, the third

finger of the left hand acting upon the key of the A natural, and the

third finger of the right hand upon the key of the lower E natural; and

also a mode of operating on the lower E hole by means of a key put in

motion by the thumb of the left hand.

Secondly my Invention relates to modes of connecting certain keys, so

that by operating upon one, another may be operated upon at the same

time; and this mode of acting on keys is applicable to other

instruments having similar keys.

Thirdly, my Invention relates to the application of a key to the C

sharp hole; also to the application of an additional C sharp hole and

key capable of being operated upon by the thumb of the left hand.

Fourthly, my Invention relates to so arranging the parts of a flute,

that in closing the B natural hole, or operating on the E natural hole

(which has a long key operated upon by the thumb of the left hand) the

C natural hole will be closed; or the C natural hole may be closed

separately by a lever acted upon by the thumb of the left hand, and

that the G sharp hole may be closed by closing either the G natural,

the F sharp, the F natural holes, or by a separate lever.

Fifthly, my Invention relates to the so arranging the parts of a flute,

clarionet, hautboy, and flageolet, that a clear succession of notes

according to the chromatic scale may be produced by the aid of only one

"a closed key."

But in order that my Invention may be better understood and readily

carried into effect, I will proceed to describe the Drawings hereunto

annexed.

Fiendish Plan No. 1 -

the Diatonic Flute

[This

is a flute that Siccama

certainly intended for and went on to manufacture, and is the one now

associated with his name. It is the topic of several papers

he

published.]

Figure 1 represents a flute arranged according to my Invention; Figure

2 shows the surface of part of the flute from b to c, Figure 1, as

though it were a plain surface and without the keys. And I would

remark, that in this case, although the size and position of some of

the holes is varied from the ordinary flute, the fingering as regards

the points acted on to produce the respective notes remain the same, or

nearly so, so that a person accustomed to use ordinary flutes will at

once be able to use one constructed according to this part of my

Invention.

The extended E mechanism

It will be seen that, instead of the small hole usually formed in keyed

flutes for the production of the lower E natural [at extreme right in

image above], which note in such flutes is always too weak, I have by

bringing this hole nearer to the D sharp key or foot of the instrument

obtained a hole of larger dimensions than has heretofore been obtained

when using the same fingering, and which is more equally distanced with

respect to the other holes.

The hole (E) has applied to it an open valve or key (1), which by an

arm is affixed to the axis (2), the axis (2) having an arm (3), by

pressing which the valve (1) is closed over the E natural hole, there

being a spring (4) [under the arm 3], which has a tendency to keep the

valve (1) raised, except when the arm (3) is pressed upon.

The Short F mechanism

The valve (5) of the hole F natural is connected by an arm to another

axis (6), that axis having an arm (7), by pressing on which opens the

valve (5) of the hole, producing the F natural, there being a spring

(8) under the arm (7), with a tendency at all times to keep that arm

raised and the valve (5) closed.

[Note

that because of the

relocation of the G and F# holes, and the provision of a remote touch

for the E hole, the F natural hole no longer can be simply brought

around to the top via the usual Short F key, but needs a longitudinal

translation, in the form here of the axle 6.]

I would remark, that although I prefer the arrangement of valves here

shown and described, I do not confine myself thereto [for the purposes

of the protection of this application] so long as I am

enabled to retain the ordinary fingering in using the instrument, and

at the same time have the holes of increased size and more equally

distanced; and, by this arrangement of the hole E natural I am enabled

to bring the F sharp and G natural holes nearer together, and to have

the E natural, F natural, F sharp, and G natural holes of the same or

nearly the same size, and the same intonation or equality of tone will

be produced in those notes. The G sharp hole is also placed so as to

regularly succeed in distance those already described, and to be of the

same or nearly the same dimensions as shown.

[This

is an extraordinarily

important point overlooked (perhaps intentionally) by previous

writers. Just moving the delinquent A and E holes to where

they

should be acoustically would have been a "good enough" outcome, but

Siccama didn't stop there. He took advantage of the new

freedom

granted him by the decision to re-site holes 3 and 6 to also shuffle

the other holes into better places.

This point becomes more clear when we remember that all of the holes on

the 8-key flute are separated by 2 semitones in pitch, with the

exception of holes 4 and 5 (fingers R1 and R2) which are just one

semitone apart. Yet, when we look at an 8-key flute this is

not

achieved, because we simply cannot put up with fingers 2 and 3 being

separated by twice the distance of fingers 1 and 2.

A

glance at the schematic above reveals how this acoustical desideratum

can be reconciled with a physical necessity. The

distances

R1-R2 and R2-R3 are approximately equal (and significantly less than on

an 8-key), but the distance F#-E is double the distance G-F#.

Bravo!]

The Extended A mechanism

In the ordinary flute the hole producing the A natural note is always

too weak in comparison with the other notes. This is occasioned by the

difficulty or almost impossibility of stretching the third finger of

the left hand far enough to cover a larger hole placed further from the

head of the instrument. The hole is therefore in such

instruments

necessarily left small, to render it in tune or proper pitch with the

other notes or intervals. This defect I have obviated by employing a

valve 9 on a lever, as shown, by pressing on the end of which the valve

will be closed. This lever turns upon the axis (11), and is constantly

borne upwards by a spring (12), By this arrangement the hole for the

note A natural may be at such distance and of such size as may produce

the best quality of tone.

[Now

you'll notice that in the

drawing, the extension to the E finger has been achieved using a

longitudinal rod & axle system, while the similar extension to

the

A finger employs a centrally-located block-mounted key. This

is

another indicator of the "omnibus" nature of this application - Siccama

is hardly going to manufacture a flute employing such a peculiar

mixture of

methods (and certainly didn't go on to). He was simply

flagging

the possibilities, and asserting his right to the concepts,

independently of how they might be implemented.

In acknowledging this though, let us not miss two interesting

points. In the upper situation, note that the A key is

implemented with a "second order lever" - force, load, fulcrum - where

Siccama's actual production models involved "third order levers" -

fulcrum, force, load. Perhaps he was just keeping his options

open, or perhaps he hadn't yet come to any conclusion as to which

system would give the most efficacious mechanical advantage.

In

the lower case, the longitudinal rod & axle system offers no

mechanical advantage either way. Of interest though, it is

arranged on what we would now consider the wrong side. He

address

one of the drawbacks of this at the end of the next paragraph.]

Note.- The B flat, B natural, C natural (with long key or shake), and C

sharp, are similarly arranged in this as in the ordinary flute. The G

sharp, and B natural holes, which have now closed keys, may when

desired have open keys applied to them; and the usual long F key may be

applied by reversing the position of the small F key.

[I

doubt whether Siccama really

means B natural in the passage above, as it doesn't have a closed

key. It's possible that a typo was introduced when the

document

was set up for printing in 1857.]

Our conclusions on the

Diatonic

A very successful implementation. Because it is essentially

an

8-key, it automatically incorporates the 8-key features.

Extending fingers 3 and 6 enable it to achieve Boehm's features

too. No wonder it went on to become the big seller it

was. If we take the 8-key as standard, it is a little more

complicated (10 keys rather than 8). Even so, a score of 6

out of 7.

Fiendish Plan No. 2 - a

key-assisted chromatic flute

[Note: Siccama gives no name for this arrangement.]

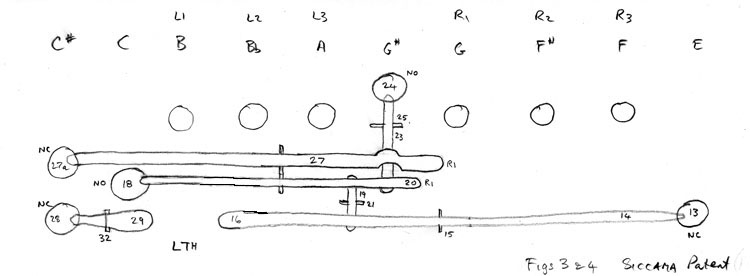

Figures 3 and 4 show the part from b to c of another arrangement of

flute according to my Invention. The parts from a to b and from c to d

of Figure 1 are suitable to be applied to this.

[In

other words, he's showing us a different body, but the usual style of

head and foot would work

with them.]

The hole for the production of the lower E is similarly placed as in

the Figure already described [i.e. optimally], but it has applied to it

a closed valve (13) at the end of the lever (14), which turns upon the

axis (15), and the valve (13) is raised by the thumb of the left hand

pressing on the end (16) of the lever (14), there being a spring (17),

which has a tendency at all times to keep that end raised.

Depressing the end (16) of the lever 14 [also] closes the valve 18 over

the C natural hole, there being a short lever 19 placed between the

lever 14 and the lever 20. On one end of this lever 20 the valve 18 is

affixed. The short lever 19 turns upon an axis 21, with one end under

the lever 14, and the other under the lever 20, as shown.

The valve 18 has a tendency at all times to remain open by the spring

22; and when I desire to close the valve 18 over the C natural hole

(without opening the hole E natural by depressing the

opposite

end of the lever 14) I can do so by means of the lever 23 of the valve

24, the lever 23 having two projections 25, 25, at right angles

thereto, which are supported in bearings 26, 26, forming the axis of

the lever 23, as shown. The one end of the lever 23 passes under the

lever 27, which is bent out of the way for that purpose, so as to come

under and be capable of raising the end of the lever 20, and thereby

close the valve 18.

27a is a valve at the end of the lever 27, which is constantly closed

by the spring 27b, and it is raised so as to open that hole by the

first finger of the right hand; 28 is a valve on the end of the lever

29, closing an extra hole, by which I can produce an additional C sharp

note when desired, according to the third part of my Invention. This

valve is closed by a spring 30, and raised by the thumb pressing on the

end 31 of the lever 29, which turns on an axis 32.

Our Conclusions on the

Key-assisted flute

Siccama seems to have made a conscious decision to give the three

strongest fingers of each hand to three adjacent semitones, thus

definitely scoring on convenience of reach but wiping out on retention

of the old fingering. And note that L4 doesn't even get

used. Marginally more complex than the 8-key - same number of

keys but two of them interact. So a formal score of 5 out of

7, although given the outcry over the minor change in fingering

introduced by Boehm, the radical rearrangement shown probably

constituted a knock-out blow.

Fiendish Plan No 3 - A

ring key chromatic flute

[Again,

Siccama gives no name for

the flute.]

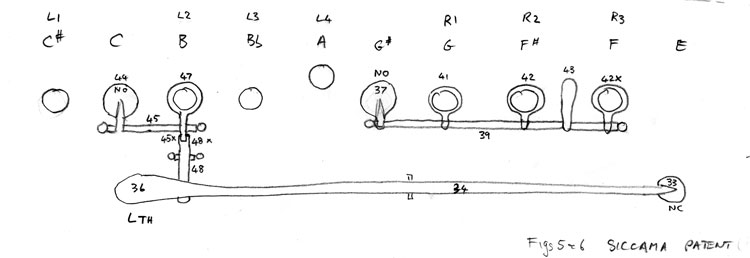

Figure 5 and 6 show part of a flute arranged according to the fourth

part of my Invention, and I have in this, as in the last-described

instrument, shown only that part to which the Invention applies, the

parts a, b, and c, d, of Figure 1 being suitable to be applied to this,

as is well understood

[As

in the case above, he's only

showing the body, the foot and head being normal.]

In this case the lower E is covered by a valve 33 on the long lever 34,

the valve having a tendency to keep closed by the spring 35, and being

raised by the thumb of the left hand pressing on the end 36 of the

lever 34.

But although I prefer the parts of the flute to be arranged so that the

E natural hole is closed except when operated upon by the thumb of the

left hand, they might be so arranged, as that, in pressing on the long

lever 34 by the thumb of the left hand, the lower E hole

would be

closed.

[Keeping

his options open! The omnibus rides again.]

The right-hand mechanism

37 is a valve over the G sharp hole; this valve is kept open by the

spring 38 except when closed by the fingering, and it is affixed by an

arm to the axis 39, which turns in the bearings 40, 40.

41, 42, 42x are rings affixed to and forming arms on the axis 39, so

placed as that when the first finger of the right hand closes the G

natural hole, or the second finger of the right hand closes the F sharp

hole, or the third finger of the right hand closes the F natural hole,

one or the other of those rings will be depressed, closing the valve 37.

The valve 37 may [alternatively] be closed by either the second or the

third finger of the right hand pressing upon the arm 43 on the axis 39.

The C natural hole is closed in a similar manner by a valve 44, affixed

to the axis 45, with a tendency to remain open by means of the spring

46.

The left-hand mechanism

To the axis 45 is affixed the ring arm 47, which is arranged over the B

natural hole, so that when the second finger of the left hand closes

the B natural hole, the ring 47 will be depressed and the valve 44

closed [producing the note C].

The first finger of the left hand may be used to close the C sharp hole.

It will be seen that there is a lever 48 with projections on each side,

forming the axis, supported in the bearings 49, 49. This lever is so

arranged as that one end passes under a short arm 45x on the axis 45,

and when the end 48x of that lever 48 is depressed it will close the

valve 44; and the long lever 34 is arranged so that by depressing the

end 36 of that lever the lever 48 may also be depressed, or the levers

48 and 35 may be independent of each other.

[This

permits the left thumb to

open the low E key, or close the upper c key]

And this arrangement of the keys is applicable to other instruments

having similar keys.

Our Conclusions on the

Ring-key flute

Another flute with an unusual fingering - not quite as radical as the

predecessor, but still radical enough to create panic in the market

place. And more demands on the left hand, so I'd be looking

at a score of less than 5 here too.

The Chromatic Flute

[Not

identified in this document

by Siccama as his "Chromatic Flute", but readily identifiable by its

drawing and description.]

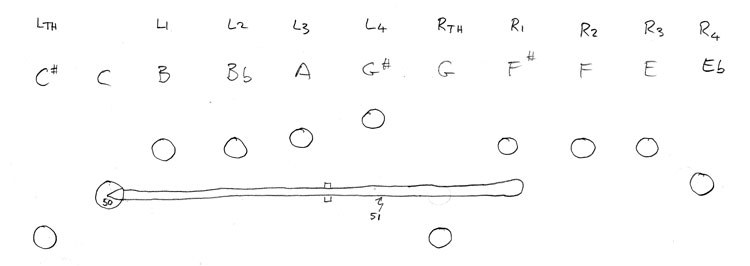

Figures 7 and 8 show a flute arranged according to the fifth part of my

Invention. The signs on the holes indicate the notes which they are

intended to represent; and it will be seen by reference to the Drawing

that by this arrangement of flute I am enabled to obtain a succession

of notes according to the chromatic scale, which I have found to be

clear and full with the aid only of one key. The valve is kept closed

over the hole producing the note C natural by the spring 51, and is

relieved by the first finger of the right hand, and the G natural hole

is acted upon by the thumb of the right hand, and if desired an open

key may be applied thereto and acted upon by the thumb of the right

hand. The C sharp hole is closed by the thumb of the left hand.

This arrangement of parts is equally applicable to the hautboy,

clarionet, and flageolet, and a workman accustomed to this class of

wind musical instruments will readily make those variations which are

consequent on a different form of instrument, and a foot with keys may

be applied to a flute arranged according to this part of the Invention

if desired.

Our Conclusion on the

One-key Chromatic

Achieving a keyless chromatic flute has been a long-term dream of

flutemakers, and rightly so - nothing provides the same intimacy of

control as a naked finger over a simple hole. Unfortunately,

neither mathematics or physics are on our side - we don't have enough

fingers to go round and they don't have enough stretch to achieve the

job without pain. I think it is fair to say that no keyless

chromatics have ever achieved what we need to achieve in a practical

flute.

In this flute, Siccama has conceded on the maths and gone with a key,

rather than to take Giorgi's approach to use the side of the hand as a

surrogate appendage. But he has employed all 8 fingers and 2

thumbs, achieving the needed 11 control points with the familiar R1 key

for C. So he definitely loses on stretch and standard

fingering, while picking up on minimal complexity. Again the

score must be well below 5.

But hey, fair's fair!

It could fairly be argued that a 1-key flute like this should really be

compared with the earlier 1-key baroque flute. In that

competition, Siccama's flute would win hands down on power, tuning and

uniformity and draw on complexity. It would be a very

different instrument, sounding like a big Siccama flute and not a

gentle baroque flute.

The imponderable is how well players could come to grips with the new

fingering pattern - a matter which perhaps need to be put to practical

test rather than left to applied ignorance. At this time we

know of none having been made.

Siccama's Conclusion

Having thus described the nature of my Invention, I would have it

understood that I do not confine myself to the precise details, so long

as the peculiar character of either part of my Invention be retained;

but what I claim is:

- First, the closing the

E natural, also A natural holes each

with a key, by which I am enabled to enlarge those holes, as herein

described; also

- I claim the operating

upon the lower E natural hole by a

key acted upon by the thumb, as herein described.

- Secondly, I claim the

modes of operating upon one key by

means of another, as described in respect of Figure 3, such improvement

being applicable, as herein mentioned, to other wind musical

instruments where similar keys are used.

- Thirdly, I claim the

applying an additional C sharp key, as

described in respect to Figure 3.

- Fourthly, I claim the

modes of connecting the keys of a

flute and other wind instruments having similar keys, as herein

described in respect to Figures 5 and 6.

- Fifthly, I claim the

arranging the parts of a flute,

applicable also to a hautboy, clarionet, and flageolet, as herein

described in respect to Figures 7 and 8.

- Also I claim the

applying the hole G natural so as to be

acted upon by the thumb of the right hand, and the applying the C sharp

hole so as to be acted upon by the thumb of the left hand, applicable

to the aforesaid instruments.

[Again,

a restatement of the individual issues that are the subject of the

application, and no indication that Siccama was thinking of four

practical instruments.]

In witness whereof, I, the said Abel Siccama, have hereunto set my hand

and seal, this Thirteenth day of September, in the year of our Lord One

thousand eight hundred and forty-five.

ABEL (L.S.) SICCAMA.

Our Conclusions

Our scoring suggests that the Diatonic flute is well ahead of the rest

of the four instruments shown in the document, and that certainly

tallies with the history. As is shown elsewhere in our

section on Siccama, the Diatonic proved massively popular and was

Pratten's easy jumping-off point for his range of Perfected

flutes. It might be disappointing that it didn't reach a

perfect score of 7 out of 7, but no flute before or since has

either. The 8-key scores only 4, Boehm's conical only

3. Boehm's later cylindrical would score a 5, and Pratten's

later multi-key flutes no better than Siccama at 6. I think

Siccama could be happy with that result.

Back to McGee Flutes home page...

Created 18 April 2009