Chapter

III.

In

the few remarks I have yet to make upon the flute's construction

generally, I shall not stop to inform the reader, as others have done

before me, of certain acoustical requirements, theories and what not,

nor shall I tell him that I have submitted the flute to diverse

experiments, but shall at once proceed in plain language to give, from

practical experience, a free and independent opinion upon the matter. The

old fingering is decidedly the best, under certain modifications,

because it is formed upon the pure and simple law of nature; the passing

from one octave to the other was difficult, and in the upper octave some

cross fingerings were of necessity awkward, but mechanism has overcome

these few objections, and I submit again, with all deference, that

nothing but difficulties and complications arose in every case where the

principle of the old or natural fingering was departed from. In

the second place the system of equal sized holes, which has been so

strongly insisted on, cannot be laid down as a fixed one because the

form of the flute will not in every case admit of it. It

appears to be an established fact that every tube which is made for the

conveyance of sound shall contain within itself a medium of resistance,

so as to give an additional impulse to the vibrations of air as they

pass through it. This has

been done from time immemorial by means of a conical shape in the flute;

at the same time the long shape of the cone offered rather more

resistance than was needed, and prevented, as an organ builder would

say, the notes from speaking with sufficient freedom.

A cylindrical form of flute, it was thought, would remedy this

evil, and has now been for some years in general use.

The idea was no doubt taken from the form of the old metal fife,

but this is of little consequence; it is sufficient that Boehm of Munich

sent a practical model of the instrument into this country (though not

the first of its kind), and that patents were taken out for its

manufacture. I

am not going to discuss the relative merits of cone and cylinder, metal

and wood, but I shall show upon what principles the first of these two

agree. I have said that tubes for the delivery of sound require a

certain graduation within themselves, so as to increase the intensity of

the vibrations of air; the cylindrical tubes of an organ are slightly

curved in the centre for this purpose, so as to give a resistance at the

apex. The difficulty

experienced in the cylindrical flute was that, being a tube for the

conveyance of more than one sound, any curve or belly in the centre of the

instrument would hopelessly interfere with its general tone.

This, however, was overcome by the invention of a head-joint,

into which a curve was introduced a little below the embouchure, and it

served the purpose named; it was the simplest of all inventions; it was

merely the carrying out of nature's laws, and it can be seen now in

practical use on all organ pipes. The principle once understood and practically carried out left little more to be desired - as one would think - but not so. The flute was found to be wanting in the one great feature of equality - no two notes were alike, some were free and full, others uncertain and feeble. The low C natural, for example, was a fine note, the D above it weak. As might be expected, this radical defect has, in spite of all endeavours, served for years to lessen its general and popular use; it is not to be supposed but that every possible kind of experiment has been tried for the purpose of reducing the cylinder to a just and equal temperament. And the inventor himself appears to have been quite as much puzzled as everybody else in arriving at the true causes of the evil; the so-called principle of large and equal-sized holes having struck such deep root into the fancy of modern makers, very great attention was paid to this particular, and all improvements, alterations and experiments appear to have been chiefly directed not to where the evil really lay, in the body of the flute, but to the head-joint alone. I

have already hinted at the necessity there is that tubes which are made

to produce successive musical sounds should have a relative graduation,

both in size and length; if we would construct a chain of pipes intended

to give out the musical scale, each pipe according to the note assigned

it would have to be shorter and smaller, or longer and thicker than its

neighbour; in plain words, the diameter of the pipe would have to be changed in proportion to the

length. A

very simple and convincing experiment will prove this.

Let a pipe of any given length be placed in the wind-chest of an

organ, whose length and diameter shall be in such a true corresponding

ratio, each to other as is necessary for the production of a pure sound;

the pipe will then deliver its note, or speak with accuracy and freedom.

Divide this same pipe or tube at its centre in order to get the

octave above; the length is now reduced by one-half, but the diameter

still remains the same. Adjust this same portion of pipe, as before, in

the wind chest, and it will require a double force of wind to make the

note speak, and even then the quality of sound elicited will be impure

and uncertain. The

result of this experiment is very easily explained.

When the pipe was shortened, it ought at the same time to have

been narrowed or constricted in size, in order to have carried out the

same conditions as the first one. Precisely

the same principle obtains in all tubes, whether flutes or otherwise,

and herein lies the real cause of the failure above mentioned. In

the first patentee's explanation of the Cylinder Flute, I find the

following statement: " It is also clear

that the nearer the holes are in size to the diameter of the tube the

freer and finer must be the tone." Had

he said, "divide an organ

tube at its centre, and it will give you the octave above," he

would have been just as near the truth as he is in the opinion I have

quoted; if you cannot by natural means vary the diameter of a cylinder

flute, which it is plain you cannot, the

statement he hazards as to the propriety of making the holes extend to

the edge of the diameter, in order to get a full and freer tone, is

plainly contradicted by the organ experiment I have just given.

Perhaps

no greater folly was ever so perversely held by flute makers generally

as the supposition that the more equal were the holes the more equal

must be the tone. I will

use their favourite term for once and say that it is decidedly contrary

to theory, and also of course

to practice. In the case of

stringed instruments we see another instance of this fallacy; as the

strings become shorter so do they lessen in size or thickness, in order

that the vibrations of sound may be rapidly produced.

Indeed, it is hardly necessary, were it not for the surprising

neglect of this principle shown in the old cylinder flute, to dwell

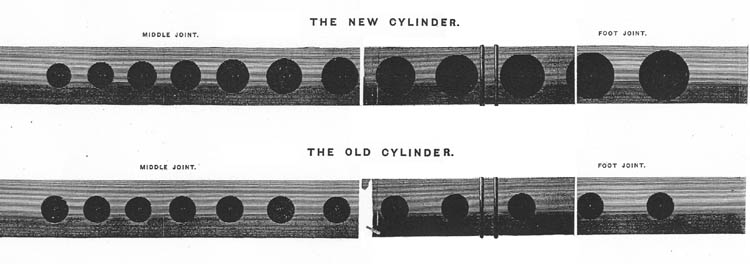

further on a matter so obvious to common sense and daily practice. Within the last few weeks, I have seen a newly constructed cylinder flute which I believe has been invented and patented by Mr. Clinton, in which these requirements, so long overlooked, are substantially carried out. To save the trouble of a long explanation I herewith give a drawing of the position and size of the holes.

The

idea has evidently struck him of effecting the object of the cone and so

to reduce the diameter of the tube with each successive note by the very

simple process of graduating the holes, not as in the old flute by a

variable scale, but equally and regularly.

Thus the small opening of the holes, or the partial excision at

the top of the instrument, serves practically to shut up or lessen the

diameter of the tube, and therefore, as each note rises, the orifice

becomes smaller through which the sound is delivered and the closing up

of the diameter becomes gradually less and less, proportionate to the

end required. The theory (I

will use the term once more) seems to me a sound one, but in flute

manufacture, practical results are the all-important tests.

To these tests I have submitted it and, in conjunction with many

other players, am satisfied that a most important end has been gained. If

perfection can ever be looked for in so restricted and complicated a

piece of mechanism as a flute, I think we shall find it here, because

there seems to be a practical reason and a sensible foundation for all I

have seen in this new improved cylinder flute. Unquestionably a

principle founded on nature's laws has been ingeniously carried out in

it and, so far as my judgment leads, it is and will be the principle and

model of all future instruments of the same class. I

do not, speaking of this Flute, lay any stress at all upon the nature of

the fingering used, for this must be an after consideration for those

who make and those who play, but I do say with confidence that it is as

yet the only flute I have ever seen to which the often vaunted terms of theory,

system, acoustical science, &c., &c., seem to have the

smallest application. Certain effects and defects peculiar to each

instrument must remain - the one its pride, the other its weakness, but

both acting as a wise provision to enable us to regulate our judgment as

to its value. It would, on

the one hand, be as unjust to refuse praise to the excellence of an

invention as it would be unwise, on the other, to shut our eyes to the

defects inseparable from it. It

is right, however, to form a fair and candid estimate of the whole by

both of these in conjunction, and to ask ourselves whether the combined

efforts of years of patient and too often of unrewarded experiments in

flute manufacture, have not led at last, as I think they have, to as

fair and satisfactory a result as can ever be expected in the nature of

things. I

have but one more word to say in closing these remarks: no position is

much less to be envied than that of one who, without partiality,

endeavours to take a collective glance at the different rival systems of

past years in any branch of art, and who seeks, as it were, to pass

judgment upon them. It

clearly would be impossible for such a reviewer to gratify, or even hope

to convince, one-tenth part of those who have been engaged in such

contentions. Whatever be

their worth, I have openly and, I hope, clearly expressed my own views

on the subject. Should any one who has himself added his share of industry and

experience towards the regeneration of the flute conceive offence from

any of the above remarks, I must distinctly beg to disclaim, on my part,

any such intention; should the conclusions I have drawn be in opposition

to any one's private views or interests, I have only to plead that they

are the necessary consequences of premises which they themselves have

helped to establish, and will be found to be but the natural results of

a fair, free, and open investigation of all matters under dispute. Lastly,

I beg my readers, one and all, to believe that I have endeavoured to

arrive at the truth of this much vexed question by the legitimate road

of research and reasoning, and that I have earnestly desired to examine

all its various points with discretion and good temper. WEST

DRAYTON, Middlesex, May,

1862. |