Why keep a collection?

As a flute researcher based in Canberra, Australia, I'm a long

way from the major collections of flutes. The nearest is a

moderately sized but interesting collection at the Powerhouse Museum in

Sydney, the next after that in Los Angeles. So, if I wish to

conduct continuing research on instruments between trips, it's pretty

vital to have good examples at hand.

As a flute maker, I find the collection just as

important. Some of these instruments are models upon which I base

my own flutes (eg the Boosey & Co Prattens.) But the others

have their place too, providing ideas and inspiration for my

work. The link between today's makers and the 19th century makers

was broken by many years of indifference to the wooden flute. The

old makers left us little in terms of words and tools, and so their

instruments are their only point of contact. Spending time with

their instruments is as close as we can get to spending time with

them. Rarely would a day go by without me taking down one or more

of the flutes in my collection, playing it, playing with it and just

looking at it. The full appreciation for their work drives me on

in mine.

About the collection.

The collection is small, but representative of the various

generations of conical flutes from the 19th century. You will

notice that the instruments aren't in sparkling condition, indeed they

look rather like the ones you see in the major collections. And

for the same reason - I don't want to erase important details by

unnecessarily restoring them to apparently new condition. But it

is important for my analysis work that they do play, so I'm forced to

tread the fine line between restoring and repairing.

The "Acquisitions Policy"

Unlike a museum collection, this collection can afford to be

fluid. I am prepared to sell some instruments in areas where I

have a more useful example in order to build up the collection in areas

I do not have. So please feel free to contact me if something

here takes your fancy, or if you have something you think might take

mine. I'm also happy to consider deals involving original

instruments as part payment for my own new instruments. And I'm

not too concerned about the condition of instruments as long as they

have not been extensively modified.

The Collection

In presenting the collection below, I've arranged it under

headings to permit comparison between flutes from different countries,

and flutes of a similar generation

and different generations. I should make it clear that this

"generations" thing is a convenience of my own construction.

There may be better ways to look at the period, but I think this gives

us a handle on it we didn't have before.

I'll fill in a bit about the maker, the history of the

flute and point to any interesting features you should know

about.

Section One - English

Simple-System Flutes

One-key Flute by Clementi

Boxwood and Ivory with silver key, this is probably an early 19th

century instrument, before Clementi took on manufacture of Nicholson's

Improved models. Note the small holes, permitting the

cross-fingerings necessary for chromatic operation.

One key Flute by Blackman

On first viewing, you might mistake this flute for a cheap

modern replica, but indeed it dates from the mid 19th

century. None the less, one key, rosewood and nickel-silver

mark it as an inexpensive option at this late time. Despite the

lack of undercutting that would have been normal on earlier one-key

flutes, it speaks surprisingly well.

The Blackman workshop ran from 1810 to 1882 in various London

locations.

First Generation English 6-8 Key

Flutes

This first period of the eight-key flute brings us flutes which are

very reminiscent of the earlier one-key and four-key flutes with extra

keys added. We expect to see:

- small embouchures

- very small fingerholes, undercut

- boxwood and ebony

- ivory bands

- flat plate keys or pewter plugs

Boxwood 6-key by Bilton

Bilton set up his workshop in 1826, after working with Cramer, Florent

and Key. The address on this flute, 93 Westminster Bridge Rd,

suggests it's from between 1826 and 1856. His mark, a unicorn

head, is common to a number of makers, possibly implying they all

worked from a common address, at the sign of the unicorn.

The flute is in nicely-figured boxwood with sterling silver

square flap keys and ivory mounts. Note the small finger holes,

and the incised rings on the tuning slide cover and stopper

displacement indicator. The embouchure and finger holes are

generously undercut all round to offset their very small size.

The flute speaks quietly but with firmness.

|

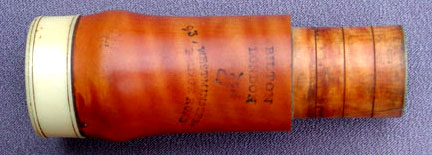

The barrel section of the Bilton, showing

the Unicorn mark and the incised rings on the slide which are intended

to match similar rings on the stopper indicator. |

|

A closer view of the foot, showing the

nicely scalloped flat plate keys in use at the time. |

Ebony 8-key by William Henry Potter

William Henry Potter was born in London on 7 Aug 1760, son of

Richard Potter

(a.k.a. Potter senior), a leading flute maker of the

time. He apprenticed to his father in 1774 (age 14!) and joined

the company as

Potter & Son in 1800, taking over in 1806. He died unmarried

in 1848,

leaving the not inconsiderable sum of 30,000 pounds sterling.

This lovely flute was made in the period 1815 -33. It is

in ebony, with ivory

bands and sterling silver keys using his father's patented system of

pewter plugs sealing into fine silver tubes set into

the tone-holes. Finger holes are fairly uniform in size - the

ratio

of hole area between largest and smallest is about 2.

|

The instrument is fitted with a tuning slide, the wooden

cover of which has three inscribed rings to mark the degree of

extension. The

fully closed position is marked "6", the first two rings marked "5" and

"4" and the third

one is unmarked),

The slide markings "4", "5" and "6"

hark back to the earlier days when different upper bodies (corps

de rechange) were supplied to handle the different pitches in

use. An

example of just such a flute by Richard Potter can be found in the Bate

Collection.

|

Second Generation English 8-key

Flutes - the "Improved" Era

Charles Nicholson the Elder ushered in the second generation

of 8-key flutes by daring to enlarge the finger holes on a typical

first-generation instrument by Astor. His son, Charles Nicholson

the Younger brought the flute to London. While everyone admired

young Nicholson's tone and power, convincing them that the flute was

the way of the future took some time and effort.

The piano and woodwind instrument company Clementi & Co

agreed to have flutes of Nicholson's style manufactured for sale

through them. The instruments were actually made by Thomas Prowse

who seems to have taken up their manufacture independently after

Clementi retired in 1831.

Once the "Improved" flutes were accepted, other makers were

quick to realise the benefits.

Hallmarks of a second generation

flute include:

- bigger holes to give better intonation and more power

- shorter lengths to achieve higher pitch

- cocus wood rather than box or ebony

- metal rings, usually silver

- saltspoon keys with "purse" pads, giving way later to

flatter cups with card-backed pads

- pewter plugs on the normally open keys, C4 and C#4

Clementi & Co C. Nicholson's Improved 8-key

Before we get too excited about the new age of big holes,

check out this apparent enigma. Proudly labelled as Nicholson's

Improved No 1403, but identical in lengths and layout with the Bilton

flute above, and with holes only a little larger.

So, were there degrees of improvement available, or was it

just good marketing? More work to be done here!

Note also the saltspoon keys on the two lowest foot keys,

where normally we would expect to see pewter plugs. Also the lip

plate, clearly added later as it partially obscures the maker's mark on

the head. The cap is no doubt a replacement - the original cap

should be covered by a ring matching those elsewhere on the body.

George Rudall, Willis Fecit, c 1820

When George Rudall returned to London from the Napoleonic wars

he took up as a flute teacher. That meant he needed a supply of

flutes for his students. He turned to established maker John

Willis for these. The flute below is marked Geo. Rudall, Willis

Fecit (Latin, literally: Willis made it.) Willis also supplied

similarly marked flutes to dealers such as Thomas Williams and Clementi

& Co.

The flute is in cocus, with silver rings and keys. The

head and barrel appear a little lighter in colour, probably due to the

finish being impaired by attention to cracks in these lined

sections. The head was probably originally unlined, as the

maker's mark appears just above but partly obliterated by the lower

ring.

This is another flute that could be argued to be a first

generation design. Supporting that view we have very small finger

holes, leather flap pads (albeit round and not square) and the vaulted

linkage to the low C key. Cocus, metal rings and a shorter scale

argue for the later category. "Transitional" would be a fair

reading, and would fit the dates well.

For more on this instrument ...

Prowse C. Nicholson's Improved 8-key

What better example of the new generation but a real Thomas

Prowse, C. Nicholson's Improved - No 3904. Visible in the picture

below are two of Nicholson's classic hallmarks - the head thinned

around the embouchure and the area around the right hand finger holes

flattened.

| An unusual feature of this flute is a long

F key whose touch bends upwards rather than downwards at the end. |

|

For much more on this remarkable flute:

C. Nicholson's Improved - the

turning point.

J.B. Cramer, Addison & Beale, T. Lindsay's Improved.

Sounding more like a company of lawyers, J.B. Cramer, Addison & Beale

were probably just the marketing agents for the real hero of this piece,

Thomas Lindsay. He is listed as a flute and flageolet maker

between 1825 and 1833. Cramer et al were set up in 1824 and ran

under that name until 1844. Our flute presumably dates from within

those limits, and possibly between Lindsay's listed limits.

This is a superbly elegant flute, with holes smaller than the

Nicholson, but substantially larger than those of first generation

flutes. Note that it is a 7-key, as Nicholson himself preferred

and recommended, and that it carries the magic Nicholsonian word,

"Improved".

Lindsay published his views on flutes, including A Few Practical Hints

B&S Dulcet Improved.

Hmmm, there's the "Improved" word again. And it becomes

clearer that these various second generation makers are using it to

imply the same thing. Because they had abandoned the idea of

equal-sized holes, second generation flutes had substantially better

tuning over most of their range compared to the earlier instruments.

The B&S Dulcet improved is a very typical medium

sized hole flute. It was the 8-key flute I learned to play on

first and so I owe it a lot. I bought it from the late Paul

Davis, a scallywag dealer in flutes and concertinas who lived just off

the Portabella Road in London. The makers are believed to be the

company Samuel, Barnett.

Metzler 8-key

The Metzler family originated in Germany; Valentine Metzler

coming to London in 1788. V. Metzler gave way to Metzler &

Son in 1816 and then Metzler & Co when Valentine died in

1833. Under the command of the son, George, the company offered

"bassoons, serpents, clarionets, flutes, drums, horns, trumpets,

trombones and bugles". George retired in 1866, the company

continuing until bought out by Cramer in 1931.

The keys on Metzler's flute bear the imprint underneath of AL

- presumed to be the wind instrument maker Alexander Liddle.

Whether Liddle actually made the flute or just supplied the keys we

perhaps will never know. Liddle is listed from 1847 to 1879 which

is getting a little late for flutes of this generation.

|

Metzler's flutes are not regarded as the

best of the period. Our example is however clearly one of the

better ones. The hand-graved sterling silver bands are not a

normal feature of Metzler flutes. Unfortunately, lack of the

customary address makes it impossible to date the instrument closely. |

On an historical note, the instrument was previously owned by

well-known London-based Irish flute player Roger Sherlock.

Rudail & Rose fake

I must admit that when I first heard of flutes being faked in the early

19th century, I was skeptical. But no more! The flute

above, provided by Adrian Duncan from Vancouver, is marked Rudail &

Rose, not Rudall. The workmanship is truly appalling. It's

a fake! For the full story on this Imposition

Upon the Public ...

Pakistani-made 8-key flute

In the late 20th century, several Pakistani firms began

manufacturing 8-key flutes, unfortunately without the benefit of

guidance or wisdom. The flute pictured above was sent to me by a

disgruntled owner, with a note asking me to do with it whatever I

thought best. It is a miserable instrument, poorly made,

out-of-tune, difficult to play. After some deliberation I concluded the

only appropriate use for it was to include it in this collection as a

warning to others.

Third Generation English 8-key

Flutes

Third generation flutes are more likely to show some of these

features:

- single piece body

- cocus still the dominant timber

- nickel or German silver sneaking in

- some post mounting

- shorter again than 2nd generation

- flatter keycups with card-backed pads

- pewter plugs retained for the two lowest notes

It's my feeling that Boehm probably ushered in the third

generation of 8-key flutes, but if so, it was unintentional.

Having been dismayed by the power that Nicholson could achieve on his

large-hole flute, Boehm was inspired to produce his 1832 conical

flute. It didn't catch on for a number of reasons, but it set a

lot of people thinking. One of these was Abel Siccama.

Siccama system 10-key, by Siccama

While Boehm's 1832 system flute was underpowered for English

taste and strayed too far from the old fingering, Siccama's subsequent

and patented Diatonic Flute satisfied both criteria but also delivered

better intonation than preceding instruments.

Our particular example is Siccama No 321. It bears the

screw-cup keys - a characteristic hallmark of Siccama's flute maker,

John Hudson.

See The Siccama Flute Story for

more on this flute and the two men who brought it to us.

Boosey & Co R.S. Pratten's Perfected 8-key

One of those who fell under the influence of Siccama's flute

was the rising young star performer, Robert Sidney Pratten. He

stuck with the Siccama for about 10 years, then went back to Siccama's

man Hudson and had him make a few changes and revert the Siccama flute

back to an 8-key. The result was marketed as RS Pratten's

Perfected.

Hudson left Siccama and went out on his own for a while, then

was snapped up by the new company of Boosey & Co, serving them as

foreman and continuing production of the Pratten's Perfected. Our

example is Boosey & Co RS Pratten's Perfected No 8626. I

picked it up in Sydney in about 1973 for AUD $25. Seemed like a

good idea at the time. Note that the metal used is Nickel Silver

The Pratten's Perfected is aptly named. All of the

previous serious problems with intonation have been dealt with in this

design. My Prattens Model and

Prattens Plans are based on this flute.

Rudall & Carte 8-key, No 7120

Now this flute is a bit of an enigma and perhaps should be

included under 2nd generation 8-keys. Yet, despite its decidedly

2nd generation look, it features 3rd generation performance. The

riddle is perhaps resolved when we discover its date of birth - 27

February 1893. This is some 46 years since Siccama and very

late for a flute of its appearance. Significantly, the length of

this flute is about the same as the RS Pratten's Perfected.

For much more on Rudall & Carte, and its

illustrious predecessors, see Rudall, Rose,

Carte & Co - the eight key flute years

Fourth Generation English 8-key Flutes

When Boehm's 1847 cylindrical flute finally

became established, diehards for the 8-key system attempted one last

stand - fit the familiar old keying system to the new cylindrical

bore. Needless to say, it didn't achieve any of Boehm's real aims

- improved venting and the like. But it sure kept the price

down!

Cylindrical bore 8-key by Moon

Moon of Plymouth was probably not a maker, but a

retailer who had instruments stamped for him. So we don't really

know who made the flute below. It mixes some typical 8-key

features with some typical Boehm features - the "parabolic" head, the

smaller embouchure, the cylindrical body, the short tuning slide

integral with the top tenon. Note at last we have lost the pewter

plugs on the bottom two notes.

The colour difference between body and head is

noticeable in real life but not to the extent our picture shows.

| The size of the bore can be better

appreciated in this comparison of the foot ends of the Moon and

Nicholson flutes. |

|

Cylindrical Old-system flute by Rudall Carte

Similar in principle to the Moon 8-key cylindrical above, this flute

employs Siccama's approach of extending the third finger of each hand

with a key. This substantially reduces discomfort while improving

tuning and response. The Boehm foot is a considerable improvement

over the old grasshopper's knees foot, and there are trill keys

giving the notes D" and E".

Cylindrical English Old-System Flute

This anonymous old-system flute originally employed keys over every

hole, but as you can see several haven't made it this far.

Although looking complex, there is no interaction between the

keys, so the operation is simply 8-key.

Section 2 - French Simple System

Flutes

By the start of the 19th

century, the French seem to have settled on the 5 key flute with short

D foot as their standard. But anywhere development seems

unavoidable.

French 8-key

This flute purports to be Australian made, bearing the mark

"Nightingale / A.P. Sykes / Melbourne". It is clearly a typical

French 8-key (the long F is missing) and was no doubt made in France

and re-badged for sale in Australia. Note that the hole sizes are

similar to the German flutes' and the English flutes before

Nicholson. Special thanks to Colin Goldie (Overton Whistles) for

getting this repatriated to Australia.

Tulou's System Perfectionee

A Tulou System Perfectionee, made by Buffet Crampon. Essentially

a French 8-key plus trill keys for D and E, a duplicate C key operated

by L3, and the characteristic F# sharpening lever operated by R3.

This flute employing stand-alone keys, some Flutes Perfectionee

employ rod & axle construction, and some a mix of both. This

flute was a French Conservatoire reaction to Boehm's instruments - a

last ditch attempt to retain small holes and soft dark sound.

Section 3 - German Simple-system

Flutes

Given Germany's auspicious

history in the development of the flute, the 19th century was less than

inspiring, with the obvious exception of Herr Boehm. Cheap,

usually anonymous German flutes flooded the world market, particularly

in the US. The Sears Roebuck catalog carried them for about $5

for an 8-key, around 1900.

Simple 19th century German 1-key flute

A typical German 4 key flute.

German 8-key flute, ivory head, cocobolo body (the barrel is a

temporary replacement).

German 12 key flute. In addition to the more typical 8 keys,

there is a trill for E, a second G# operated by the left thumb, a

second Bb touch for R1 and a low B operated by L4. Note also the

line-up dots at each junction.

A Schwedlerflöte, the jumping-off point for the German Reform Flute

movement. Very similar to the 12-key flute above, apart from the

Brille mechanism to sharpen c#, Boehm-style foot keys, the metal head and

ebonite "reform embouchure".

Section 4 - American Simple System

Flutes

Pond 6 key

A flute by Wm. A. Pond, 47 Broadway, New York. Marked "German

Silver". Essentially similar to the Firth & Pond which was the

subject of my Interesting Collaboration with Grey

Larsen, and lead to the introduction of my Grey

Larsen Preferred range of flutes.

Section 5 - Boehm System

Flutes

Theobold Boehm was by any account a remarkable

man - Schafhautl's concise biography translated and reprinted in

Christopher Welch "History of the Boehm Flute" leaves no other

interpretation open. Boehm made two major forays into the flute

world - his conical instrument of 1832 and his cylindrical instrument

of 1847. Both created Tsunamis.

Conical 1832 Conical Boehm by Laube.

This French made flute would date from the end of the 19th

century. While Boehm's 1832 conical design didn't catch on in

England, it was received much more warmly by the French. Believed

to be acoustically very similar if not identical to the 1832 flute, the

system of keying is much more similar to that used on the modern Boehm.

| An interesting feature of Boehm's 1832 instrument

perpetuated in the Laube is the use of two small tone-holes at the

thumb c key, needed to stabilise third octave G. |

|

Armstrong Model 90

What flute collection would be complete without a

"plain vanilla" cylindrical Boehm flute? This one comes from my

short career

as a metal flute player.

Even this flute has an interesting tale to

tell. It was built in the early 1970s in the U.S.

where pitch had

been standardised in about 1921 to A 440Hz. None the less, the

instrument is in better tune pulled out to A 435, Boehm's pitch.

Section 6- Flutes after Boehm

Not everyone liked Boehm's cylindrical flute. Some rejected it

out of hand, others sought to use the new cylindrical bore but retain

the old fingering, at least as much as possible. One of these was

Richard Carte, who quickly came out with his 1851 Patent flute.

He revised the design in 1867. The flute below is an

example of this.

Rudall

Carte & Co, No 2443, an 1867 Patent flute in ebonite, at high pitch.

|